Multiplying two matrices is a very common subproblem in solving larger problems starting from solving a set of linear equations to training Deep Neural Networks. It is very important to do matrix multiplication with the maximum efficiency of the hardware platform. In this series of blog posts, I am trying to find the performance of the simplest 3 loop implementation of matrix multiplication and compare it with that of libraries used in the industry. I will also discuss the bottlenecks and how we can approach the efficiency of industrial-grade high-performance math libraries using our knowledge of the CPU architecture.

Introduction to Matrix Multiplication

An Example of Matrix Multiplication

An Example of Matrix Multiplication

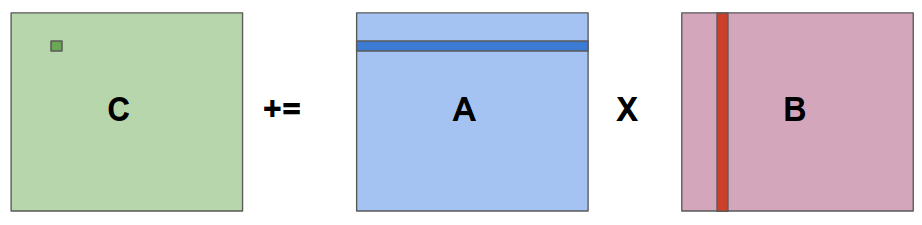

Consider the above example of matrix multuplication. We want to multiply the matrices A and B and save the result in the matrix C. (i, j)th element of C can be found by taking the dot product of ith row of a and jth column of B. And if we do this operation for all the i x j elements of C, we will get the resultant C matrix.

for(i=0;i<r;i++)

{

for(j=0;j<c;j++)

{

C[i][j]=0;

for(k=0;k<c;k++)

{

C[i][j]+=A[i][k]*B[k][j];

}

}

}

The above loop nest will do the same thing and find the answer. Now let us see how this code performs. For multiplying two 2096 x 2096 matrices, the above code took 1230 seconds on my laptop. But when I used Intel’s MKL library to do the same operation, it only took 3.6 seconds! That is a huge difference. instead of MKL, if you use something like Numpy in python to do the same operation, but you will also get time measurements that are comparable to MKL’s running time. In this series of blog posts, we will see why our code is bad for performance, what is preventing it from utilizing the maximum capacity of the CPU and how libraries like MKL overcome these problems and achieves a tremendous performance improvement. MKL is a proprietary library and we don’t know what they are doing. But we have opensource libraries like OpenBLAS and BLISS which has almost the same performance as MKL.

Finding the sources of inneficiency

Cache Behaviour

We know that modern CPUs work on a hierarchical model of memory. The main memory is accessed through levels of cache to reduce memory access latency. x86 machines we have in the market have 3 levels of caches L1, L2, and L3. The following table shows

| Level | Access Time |

|---|---|

| L1 Cache | 0.5ns |

| L2 Cache | 7 ns |

| L3 Cache | 20 ns |

| Main Memory | 100 ns |

Memory access time increases from L1 to L3 and access time is significantly high if the data has to be fetched from main memory. It is two orders of magnitude higher from L1 cache access time. If CPU is waiting for an operand from the main memory, it will essentially waste 100s of its valuable clock cycles without doing anything useful.

Caches usually use something similar to LRU(Last Recently Used). A new line is brought from the main memory to the innermost level of cache when that line is accessed for the first time. If needed cache will evict the last recently used line for this. Also note that cache operates in the granularity of cache lines and the whole line is brought to the cache when anything inside the line is accessed. A cache line is 64 bytes in the case of x86 machines that we use.

Lets have a close look at the code snippet above and try to figure out how this will behave in the cache. In C matrices are stored in row major order. The memory accesses of the first matrix in row wise. When a single digit is access, adjascent digits that are in the same cache line are also brought to the cache. This will speed up the consequent accesses. But the memory access pattern of matrix B is colum wise and this is really bad for cache.

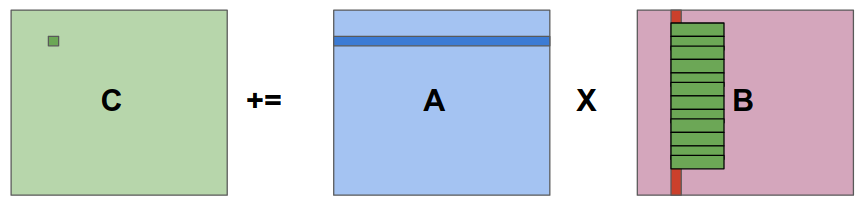

Consider that the green boxes inside the matrix B are the cache lines. Each element in the column we are considering is in a different cache line. Accessing any element in the row will require memory access which is costly. Between two multiplications(of an element of A and an element of B) there is memory access and this will waste hundreds of CPU cycles. As you can see, CPU is spending most of its time waiting for data from memory to arrive rather than doing actual computation. At this point, it doesn’t matter how fast is your CPU, the real bottleneck is memory access latency.

Now consider the computation of the next element of C. For this next row of A and the next column of B has to be accessed. Since the cache lines of B are already in the cache(Green boxes in the above figure), you might think this time the elements are present in the cache and computation can proceed smoothly. If the matrix B is large enough and it has more rows such that cache cannot hold that many lines in it, by the time you reach the last element of a column, the first cache line would have been replaced. Therefore the entire column has to be fetched again from the main memory every time you calculate an element of C. Here you can see another inefficiency, we are bringing in same element of B, again and again, to cache without utilizing the spacial locality in any way. This is a perfect example of how not to use the cache!

Effects on TLB

All modern CPUs use virtual memory and paging. Whenever you have to access memory, the virtual address issued by the instruction has to be translated to physical address. For this translation, CPU might have to have up to 5 memory accesses to traverse the page table data structure. This is a very costly operation and CPUs will have TLBs that store most recent translations. Accessing TLB is a low latency operation and TLBs help improve performance greatly. There can be more than one level of TLB as in the case of cache.

If the matrix we are considering is large enough, it will span over a number of pages in the main memory. Since the page size is usually 4kb and a double-precision floating point number takes 8 bytes in memory, a page can only hold up to 512 double-precision floating point numbers.

As an example, consider a matrix of size 2048x2048. Each row of this matrix will have 4 pages. Thus the whole matrix will take 2048 * 4 pages in the memory. Now consider the access pattern in the B matrix. Clearly each element in a column is on a different page. And the TLB will not be as big to hold all of these translations by the time you reach the end of the column. For accessing the next column, CPU will not find that translation in the TLB and it will again have to access memory to do the virtual to physical address translation. Here you missed all the advantages of having a TLB and increased the number of costly memory accesses.

Missing the Benifits of Prefetcher

When CPU is accessing memory continuously or in some predictable fashion, there is a component called prefetcher that will proactively bring in the next cache lines even before CPU access it. It hides memory latency by overlapping it with computation and this is a great source of performance improvement. For access pattern in matrix A, this works fine but in the case of Matrix B, prefetcher cannot offer you any help. Looking careful in the access pattern of matrix B reveals that they are strided memory accesses. That is, the elements of a column are spaced equally in the main memory. Prefetchers can handle this kind of memory access and predict the next address that will be accessed. The important point here is, prefetchers do not cross page boundaries. As we have seen earlier, each element of the same column is on a different page. Because of this, prefetchers will not bring in the consecutive elements of the column. (Prefetches operated on the physical address and because of this, there is a problem if prefetchers go beyond page boundaries and fetch next cache line. In the main memory, there is no guarantee that consecutive page frames have pages of the same process. Even if it is from the same process, the page might not be the next page in the virtual memory. It is because of this problem, prefetchers only operate inside a page)

Can Multithreading Help?

CPUs are equiped with more physical cores and threads these days. What will happen if we parallelize the code and execute it? Can it improve performance linearly with more threads?

Multithreading will not help in any way here. The reason is, even if you run the code in one thread, it is already hogging all of the memory bandwidth available by using the cache and TLB in a very bad way. If you add more threads to it, it will not do anything more than increasing the contention for memory bandwidth. It is a known fact that memory bandwidth is the performance bottleneck in most modern multicore CPUs. The increased number of cores and simultaneous multithreading has improved parallelism in CPU, but the memory bandwidth did not increase that much to catch up with this.

It is clear that we have to solve all the problems mentioned above to achieve a more than 100x performance boost that we are expecting. In the next 2 posts, I will discuss how we can do that by rearranging the matrix multiplication and using our knowledge about the CPU architecture.